Welcome to The Square Inch, a Friday newsletter on Christianity, culture, and all of the many-varied “square inches” of God’s domain. This is a paid subscription feature with a preview for free subscribers, so please click on the button below to enjoy this along with an “Off The Shelf” feature about books and Wednesday’s “The Quarter Inch,” a quick(er) commentary on current events.

Dear Friends,

Eclecticism is valued around here. I really do try to keep from banging away on just a single square inch of God’s domain week after week. The sound gets irritating, and it dulls the senses. There are an incalculable number of square inches to cover, and it is far too easy to slip into a kind of monomania.

I am tired of writing about Nazis and nationalists. I bet you’re tired of reading about them. So I am just going to make one more observation and then hopefully take a long break to move on to something you might find more edifying. Last week over at American Reformer a writer by the name of Ben Crenshaw wrote a sincere—if overly tedious and plodding—essay on nationalism and the American constitutional order. I was bothered by it for the simple reason that while he acknowledged the existence of “pre-political” realities and institutions (i.e., natural rights), he then seemed to imply that the moment those pre-political realities touched a human community or association—a “social compact”—they ceased to be pre-political. He writes:

What Hamilton is saying—and what is also clear from Parson’s Essex Result—is that when men enter political society via the social compact (or covenant), their natural rights are transformed into civil rights. The only difference between the two is that while the former is bound only by the law of nature applicable to man’s individual, familial, and social setting in the state of nature (in the absence of the body politic or civil government), civil rights are natural rights modified by human law to conform to the common goods of political society. In this way, a healthy political society will help actualize the common good télos of natural rights.

The first problem is that that isn’t what Hamilton said. Hamilton wrote—and Crenshaw even italicizes this portion of the quote— “Civil liberty is only natural liberty, modified and secured by the sanctions of civil society.” But Crenshaw rephrases it: “civil rights are natural rights modified by human law to conform to the common goods of political society.” He left out a very important word: secured. Civil law secures natural rights, for Hamilton—that is, it ensures their relative independence and their continued existence. For Crenshaw, civil law only modifies them by bringing them under the sovereign sway of (“conforms them to”) the “common goods of political society.” They are completely transformed by becoming subordinate to the State. Once a political society forms, the pre-political ceases to be so. Politics is like walking into Hotel California: you can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.

This is, in my estimation, a recipe for unbridled Statism. There is no discernible limit to what the government can demand of its people and her institutions in the name of the “common good.” (See, for example, what the State of California thinks of the natural rights of parents when it comes to the “common good” of mutilating children to change their sex.) Underneath Crenshaw’s thick veneer of reverence and respect for our constitutional order—not withstanding his subtle revision of Hamilton—I uneasily sense an authoritarian strain.

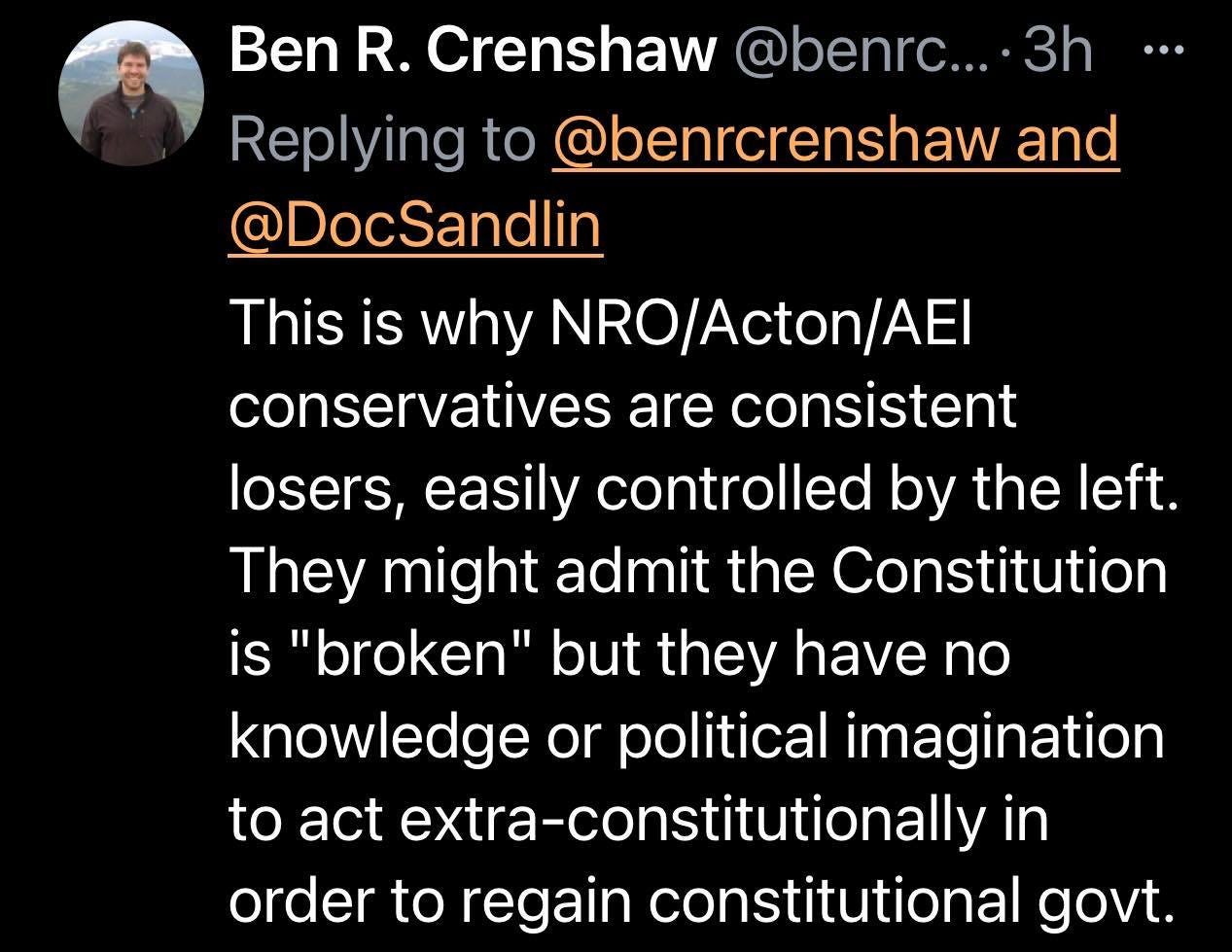

Surely that is uncharitable of me. These “American Reformers” aren’t enemies of liberty or the constitutional order; they merely want to preserve that order, right? A week later, Mr. Crenshaw Tweets the following to my colleague, Andrew Sandlin (and note the “like” by AmRef founder Nate Fischer):

Insults to movement conservatives (ignorant ones, at that) and ungrateful dismissals of their accomplishments and effectiveness don’t really bother me. Par for the course these days. But just look at that last sentence: “no knowledge or political imagination to act extra-constitutionally in order to regain constitutional government.”

There it is in plain English. The plan is to subvert the rule of law (act “extra-constitutionally) in order to “save” the rule of law (constitutional government). I am old enough to remember when conservatives used to laugh and laugh at progressives for their thick-headed, stubborn refusal to learn from history. “No, Alexandria, socialism is not going to work this time.” Now comes a so-called conservative insisting that this time the revolutionary who upends the constitutional order will do so only in order to restore the constitutional order.

Never mind that this has been the pinky-promise of every revolutionary tyrant in the last three hundred years. Sandlin responded:

The American Reformer is not really interested in reformation. They are little revolutionaries. And that never, ever, ever, ever, ever ends well.

Not to mention it is a direct violation of God’s command in Romans 13, verses 1-2.

That is quite enough of that. Let me write of pleasanter things.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Square Inch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.