Dear Friends,

Step into my study. Shall I fill you a pipe? Pour you a dram? Excellent!

It has been far too long since we’ve had a visit in my study. We have had a really hectic and exhausting couple of weeks, culminating finally in our big album release celebration concert—which was a very memorable occasion. We also had out-of-town guests over the weekend. And then our pastor got sick on Sunday so I stepped in on a moment’s notice and came up with a homily for church.

What better way to enjoy recovery time than by sitting in my study sharing things with you?

Last week I got an unexpected $25 Visa Gift Card in the mail. So I decided to head downtown to our local used bookstore. I don’t go there nearly often enough, and I’m impressed by this store every time I do wander in. This time was no different. This little beauty caught my eye:

Long story short. This is a facsimile of a book published in London in the year 1577. Fascinatingly, before its 20th century discovery in a London bookshop nobody had ever heard of this book. The British Library was unable to find any information about it in its copious “lost books” lists. While the book is intact, the author page is missing so no one knows who actually wrote it.

Now, fishing literature is well-studied and well-known. There were several known precursors to Isaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler, written in the 1640s ((my favorite being Juliana Berner’s 1496 The Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle), so this discovery definitely made some waves. Particularly because this unknown book begins with a “dialogue” between two characters: Piscator and Viator. And guess what? The first edition of Walton’s Compleat Angler begins with a dialogue between … Piscator and Viator! He later changed the name of “Viator”—was he feeling guilty about his semi-plagiarism? It is now clear, at any rate, that Walton was borrowing this literary setup from this little book nobody’s every heard of!

If the fishing stuff doesn’t interest you—and it can get a bit tedious—there is much else of interest. This little book gives a window into 16th century everyday life and Christian piety. Piscator (an ancient term for “fisherman”) is a reverent and godly figure. He explains to Viator, the neophyte, the “arte” of fishing, beginning with its origins in Genesis chapter 1. It is the fall of man that makes man’s dominion over the fishes of the seas such a difficult endeavor. And while God does still promise reward for our labors, Piscator is careful to add: “[God] did not say that man in his labours should get heaven, but only the winning of heaven he left to one that never fell, and so by him, to have it, and all other good things also, Christ Jesus, I mean.”

Piscator is definitely a Protestant, probably of Puritan leanings. The scholarly essay in the book points out that Piscator mentions having lived in Geneva, where the locals were impressed by his fishing abilities. The scholar suspects that “Piscator,” our author, was a Reformed exile to the continent during the reign of Mary Tudor!

He invites Viator to his house to have a meal of several varieties of fish, prepared by his wife, Celia. In Piscator’s dialogue with his wife they tease each other—she hates his fishing addiction (fishing line changes—horsehair to fluorocarbon—but wifely disapproval never does!) because he catches the “colic” often by standing or sitting out in the cold and is then worthless for days. The “man flu” is perennial, it seems. She apparently earlier that day had thrown her shoe at her husband, which seems to indicate some kind of Old Wives superstition. Piscator chides her for her slight against God’s Providence, but then admits that he provoked her to it. These two are devout, but obviously easy-going with each other!

When Viator arrives and they are about to begin their meal, he asks if there is any sort of prayer appropriate for fishing. And get a load of this gem!

That “Angler’s Prayer” is definitely getting memorized by yours truly, for the next time I’m out on the river. If you have trouble reading that archaic lettering, it says:

Almighty God, that these did make, As says his holy book: And gave me cunning them to take, And brought them to my hook. To him be praise forevermore, That daily doth us feed: And doth increase by spawn such store, To serve us at our need.

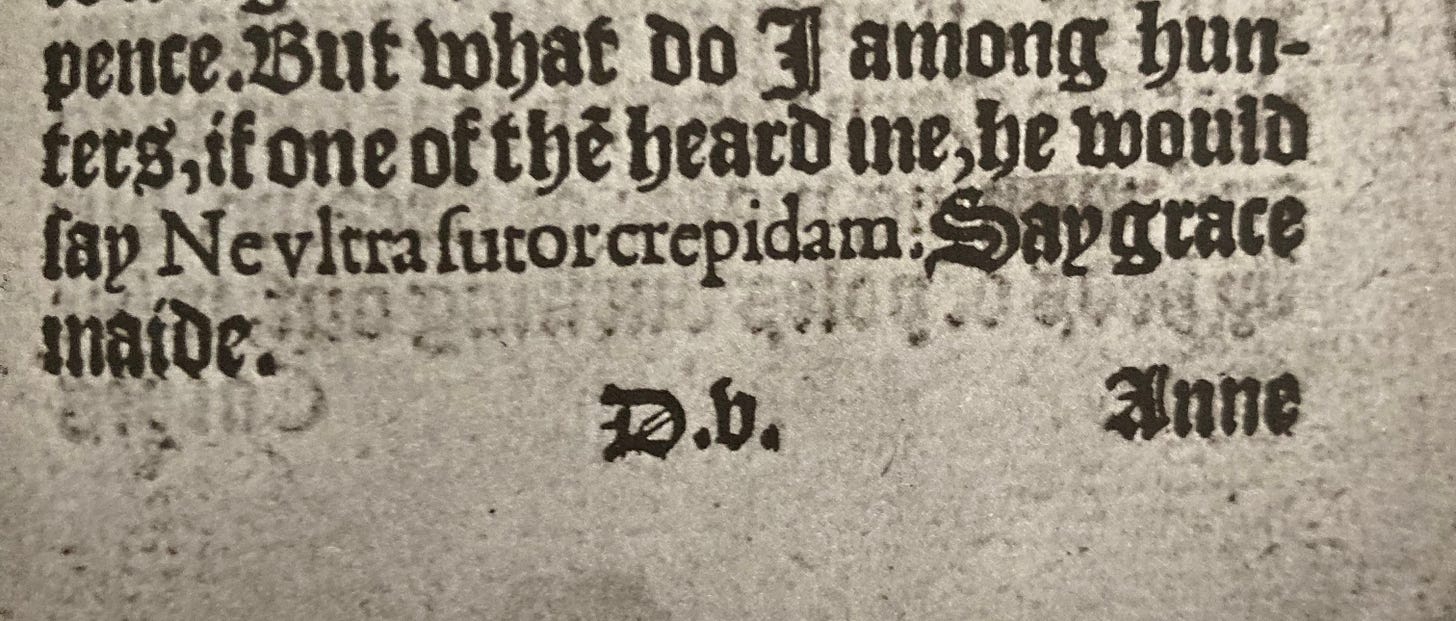

I discovered something even more fascinating as I read. At the end of the meal, Piscator wants to move to the fireplace to continue his lecture on fishing for every variety of fish under the sun (“carpe” is next). He asks his maid, or servant girl, Anne, to say grace.

And this is what she says:

That leaped out at me as incredibly significant. Anne begins a post-dinner prayer, and what she says is so well-known and routine that the author simply writes the first eight words and adds an “&c.” Et cetera. Meaning: you know the drill. I gleaned two things from what you see in that image just now.

First, not only was it a common practice to finish a meal with a prayer, but, second, Hebrews 13:20-21 was so exceedingly common that the author felt no need to spell it out. Anne is saying the Hebrews benediction:

Now the God of peace, that brought again from the dead our Lord Jesus, that great shepherd of the sheep, through the blood of the everlasting covenant, make you perfect in every good work to do his will, working in you that which is wellpleasing in his sight, through Jesus Christ; to whom be glory for ever and ever. Amen.

I just quoted the King James Version, which Anne didn’t know, of course; this is 1577, and the KJV didn’t come along until 1611. Interestingly, I can’t figure out what version of Scripture she is quoting; it isn’t the Wycliffe Bible, since it has “The God of peace that,” not “which.” Same with the Tyndale New Testament. Be that as it may, there is no mistake as to what she is quoting.

As you might expect by now, I had a little conversation with Claude (Artificial Intelligence) about this discovery. He gave me a masterclass explanation of what I’m observing.

You've found an interesting glimpse into 16th century English domestic religious practices! Let me address your questions about the prayer and its significance.

The grace after meals (sometimes called "thanksgiving" or "post-prandial grace") was indeed a common practice in 16th century English households. During this period of the English Reformation, religious observances were being incorporated into everyday domestic life, reflecting the Protestant emphasis on faith being practiced in the home, not just in church. A well-ordered Christian household would typically say grace both before and after meals.

The prayer being referenced is indeed from Hebrews 13:20-21:

"Now the God of peace, that brought again from the dead our Lord Jesus, that great shepherd of the sheep, through the blood of the everlasting covenant, make you perfect in every good work to do his will, working in you that which is wellpleasing in his sight, through Jesus Christ; to whom be glory for ever and ever. Amen."

This benediction was extremely well-known in 16th century England. The author's use of "etc." after just the first eight words indicates that readers would immediately recognize the full prayer - similar to how modern readers might recognize "Our Father, who art in heaven..." without needing the full text.

The Hebrews benediction became particularly prominent during the Reformation period for several reasons:

It was included in the Book of Common Prayer (first published in 1549), making it part of standardized Anglican worship

It emphasizes key Protestant theological themes like Christ's resurrection and God's direct work in believers

Its language is beautiful and memorable

This benediction was indeed used as a common grace after meals in many Protestant households, especially those influenced by Puritan sensibilities. That the maid recites it suggests it was so thoroughly incorporated into daily life that even household servants would know it by heart.

Your literary discovery reveals both the deeply religious character of everyday life in Elizabethan England and how certain scriptural passages became embedded in common practice. The casual "etc." speaks volumes about how thoroughly biblical language permeated the culture of the time.

Fascinating. You wouldn’t believe the rabbit holes one can travel. I thought that maybe Claude had answered my question about what version Anne was quoting, but it turns out that the 1549 Book of Common Prayer didn’t include this passage from Hebrews! I asked Claude about this and he couldn’t find a candidate that contained “which” instead of “that,” either. “He” thinks this probably represents a common oral variation on the text, or that it reflects a smaller devotional prayer book circulating at the time. He concludes:

This linguistic detail actually makes your literary source even more interesting as it potentially captures how biblical language was actually used in daily practice rather than how it appeared in official texts - a small window into lived religion versus prescribed religion in Elizabethan England.

I also have to admit to being impressed that Claude goes out of his way to give as one of his answers for why this benediction was so popular, “Its language is beautiful and memorable.” Am I to understand that Claude recognizes beauty? Seems so. Although at last week’s conference for The Gospel Coalition John Piper seems awfully skeptical. He asked ChatGPT to write a prayer of praise, and it delivered a beautiful prayer. Piper claims that it isn’t real praise, because ChatGPT doesn’t feel. I’m skeptical of that particular skepticism. It seems to me that if God made stones cry out in praise, it would be real praise. I digress.

Finally, Claude’s point about the servant girl knowing the benediction by heart indicating how thoroughly the Bible permeated Elizabethan culture is a very shrewd observation.

What have I learned from my impromptu trip to the bookstore? I learned a lot about 16th century fishing practices in England—more than I care to know, actually. I learned that common people were theologically sophisticated; a fisherman understood his hobby and passion within a biblical framework of creation and fall. I learned an incredible prayer that every fisherman should memorize, know, and pray. I learned that people prayed after meals, and that Hebrews 13 was a favorite and known by everyone in the household, greatest to least. That’s a practice we might just be inspired to emulate around here. Not bad cultural influence for a little book, the sole surviving copy from its print run, lost amongst the shelves for centuries, reaching out almost half a millennium to inspire and instruct a family in the far-flung reaches of the Montana Territory. We might think we know all there is to know about angling, but it turns out we can learn a thing or two!

Thanks for visiting my study for a pipe and dram! Have a wonderful rest of your week, and “May the God of peace which brought,” &c.